Solution for work–life balance and the gender perspective

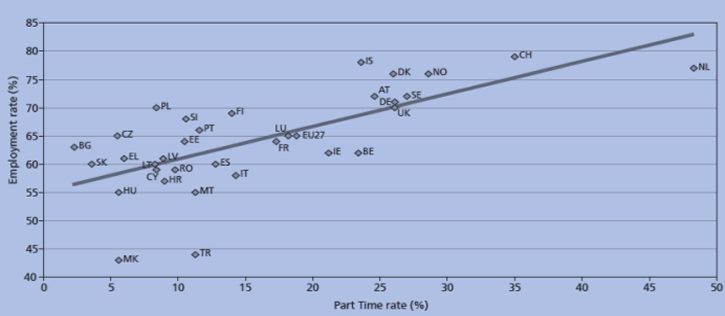

It is widely reported that part-time work may be a convenient solution for parents (especially mothers) with small children wishing to remain in the labour market. It has been found that the fertility rate is strongly and positively linked with the part-time employment rate, suggesting that part-time work indeed creates an opportunity for women to combine a job with taking care of their children.

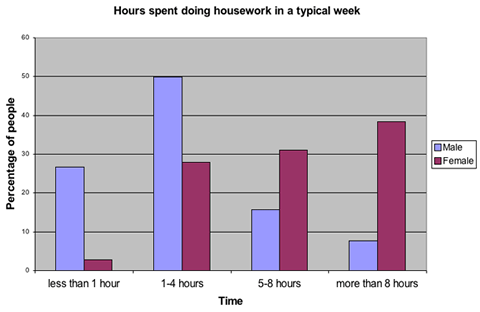

Some studies focus on the gender aspect of work–life balance. As women increase their amount of paid worked hours, men do not assume a greater share of the housework. Based on a study carried out in the Netherlands, Booth and van Ours (2010) found that there is a clear gender bias in the division of labour within the household.

Some studies focus on the gender aspect of work–life balance. As women increase their amount of paid worked hours, men do not assume a greater share of the housework. Based on a study carried out in the Netherlands, Booth and van Ours (2010) found that there is a clear gender bias in the division of labour within the household.  Where the male partner works full time, more hours worked by the female partner result in just a non-proportional decrease in housework, while male partner’s housework remains constant. This finding was confirmed by a report on the gender perspective of working conditions, based on the fourth European Working Conditions Survey - EWCS, which found that women work longer than men, especially if they work full-time, due to the unequal distribution of housework. Women working part-time also work longer than men, as they do most of the unpaid work.

Where the male partner works full time, more hours worked by the female partner result in just a non-proportional decrease in housework, while male partner’s housework remains constant. This finding was confirmed by a report on the gender perspective of working conditions, based on the fourth European Working Conditions Survey - EWCS, which found that women work longer than men, especially if they work full-time, due to the unequal distribution of housework. Women working part-time also work longer than men, as they do most of the unpaid work.

This reflects the importance of the work–life balance for women, and may explain why many studies on part-time work concentrate exclusively on women.

However, as their children grow up, they want full-time work once more. In some European countries the legal and social infrastructure allows or even

However, as their children grow up, they want full-time work once more. In some European countries the legal and social infrastructure allows or even  It has been suggested that there is a strong gender bias regarding the relationship between the number of hours worked and life satisfaction. For example, Booth and van Ours (2009) found that the life satisfaction of women who have a male partner is reduced if they themselves work full-time, especially if they work 40 or more hours. At the same time, their male partner’s life satisfaction is

It has been suggested that there is a strong gender bias regarding the relationship between the number of hours worked and life satisfaction. For example, Booth and van Ours (2009) found that the life satisfaction of women who have a male partner is reduced if they themselves work full-time, especially if they work 40 or more hours. At the same time, their male partner’s life satisfaction is  A previous Eurofound report

A previous Eurofound report  Effect on pay

Effect on pay